Let’s dress up: An essay by Bridget Foley

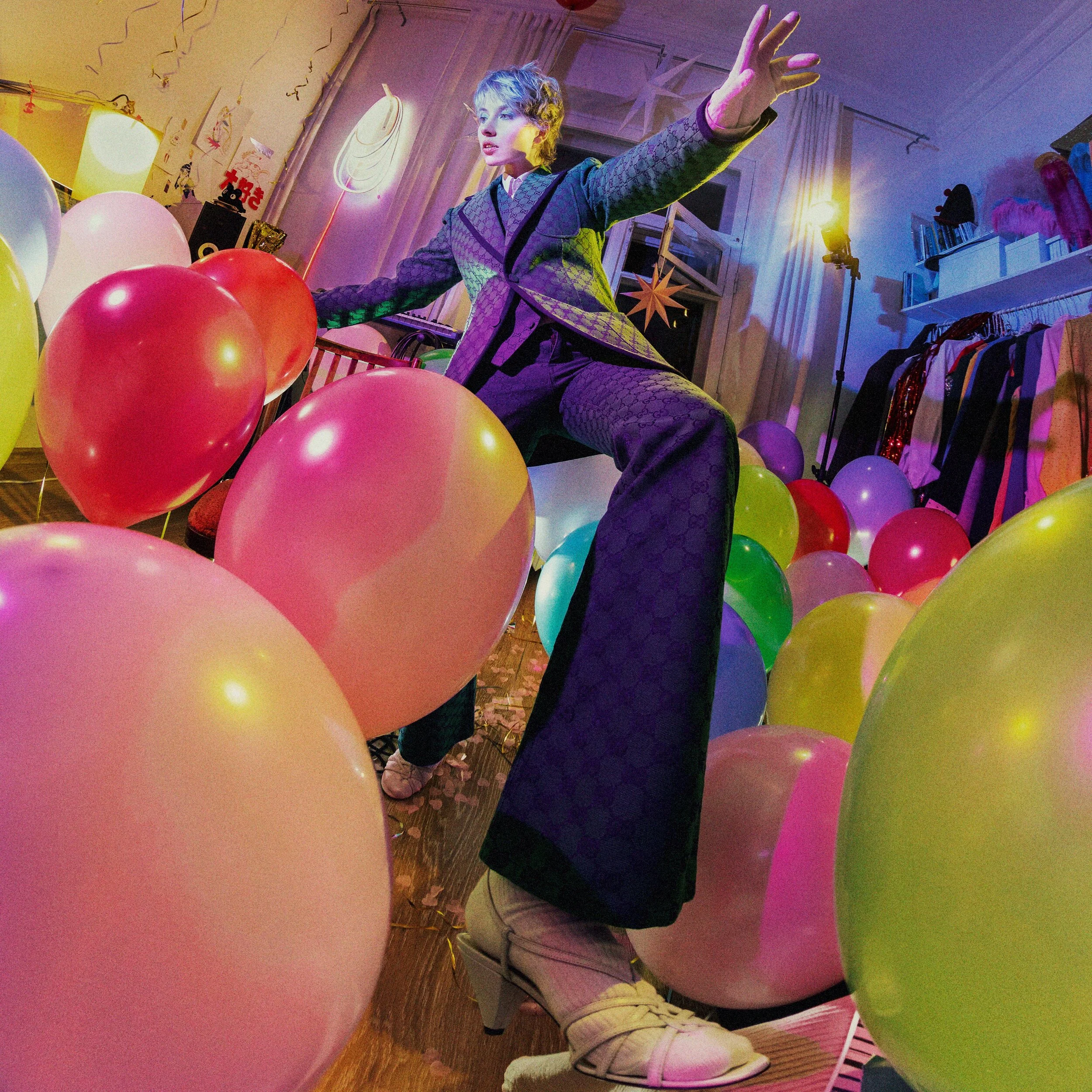

Following the social withdrawal of repeated lockdowns, couture has taken on a new and unexpected relevance. An all-consuming desire to get out and party, to be seen and be spectacular, is driving our attention to the most imaginative creations at the haute end of the fashion spectrum.

‘Let’s dress up!’ So read the invitation to the recent wedding celebration of a couple who saw their nuptial plans postponed and reimagined due to Covid-19. With no defined mandates (‘black tie’, ‘cocktail’), the wardrobe suggestion rang less as a command than as a conspiratorial call for individual expressions of shared joy via the most obvious visual markers we humans have, apart from a smile – our clothes.

The now-newlyweds are not alone in their yearning to dress up. Fashion lovers everywhere, and perhaps even some people who don’t consider themselves emotionally invested in fashion, have longed to re-embrace getting dressed after a year spent either alone or with a tight circle of dwelling mates. Joni Mitchell nailed the sentiment decades ago: ‘You don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone.’

Dressing up implies going out, seeing people, enjoying life. When we lost that, God, we missed it. Sure, some people dressed up big-time just for themselves, or to post on Instagram diversionary, feel-good images for the rest of us to like and be inspired by (or perhaps be made a little jealous) in our own too-small cloistered worlds, as we worked the at-home wardrobe of T-shirts, sweats and leggings, with the requisite waist-up flourish for Zoom calls.

Then, our worlds started to open up. Given all that Covid has wrought, one might think that, in finally reclaiming some sense of normalcy, getting dressed would hardly seem all that important. But it is. The desire to dress – we’ve thought about it, we’ve felt it, we’ve embraced emergent examples observed here and there over the past few months. We relished seeing Marc Jacobs’ autumn collection, titled ‘Happiness’, that he showed in June. We’ve watched the evolution of the 2021 red carpet, from the early awards shows with their sad-sack remote pyjama sightings to the all-out explosion of fashion at the recent Cannes Film Festival, where women and some men, too, pulled out every fashion stop they could. Top of the dazzling list: Bella Hadid’s near-immediate acquisition of Daniel Roseberry’s couture ‘lung dress’ for Schiaparelli.

We delighted as well in Lady Gaga’s Summer Wardrobe of Wonder that took street style to the stratosphere. In New York for a concert with her friend Tony Bennett, she elevated exiting the Plaza Hotel to high art with a litany of big fashion: white, ruffled Giambattista Valli; black retro-sultry Alexander McQueen; vintage pinstriped Jean Paul Gaultier; baby-blue biker Marc Jacobs; mega-sleeved, chichi Christian Siriano; billowing, floral Richard Quinn. The Lady finished off several such looks with her favourite stepping-out footwear, mile-high Pleaser Shoes. Uplifting in July and August, such a display would have been unthinkable only a few months prior. One more look merits mention: Gaga’s haute-steamy purple micro-mini cape dress and huge feathered hat, fresh off the couture runway of Valentino’s Pierpaolo Piccioli.

And so, to couture. The ‘let’s dress up’ zeal permeated the autumn 2021 collections in July, which proved a special season. It was special for starters merely because it happened at all in the traditional sense – people from around the world booked hotel rooms and boarded airplanes to fly to Paris to attend physical shows. That hadn’t happened since autumn 2020 ready-to-wear, the watershed moment after which Covid permeated our lives. The season was exciting, too, for the thrill of the new, expressed in some high-profile collections that could not have been more pointed in messaging that yes, finally, it’s time to really dress. On one level, that notion is core to the haute genre. Couture provides social clothes in the purest sense – clothes for occasions for public interaction, by day and night. That said, particularly at Balenciaga and Schiaparelli, this season provided a quite particular wow factor.

In that respect, this moment could be read as the serendipitous start of a ‘New Couture’ following emergence from lockdown. But in fact, an evolution has been in development for some time. Its early highlights are twofold. First, women couturiers now helm two of haute couture’s most hallowed and powerful houses: Maria Grazia Chiuri at Dior and Virginie Viard at Chanel. Both shoulder vast creative responsibility; bigger picture, Chiuri has famously made feminism a guiding principle of her tenure. Given the current cultural tenor, that may seem unremarkable today. However, only five years ago, when Chiuri arrived as creative director of the house, it was a major deal. Then, she proclaimed her perspective from her runway, her models wearing those now-famous T-shirts that proclaimed, ‘We should all be feminists.’ ‘For me,’ Chiuri says, ‘it was and is important to give a modern definition to the concept of femininity, with designs made for the female body by a designer who is aware of the ins and outs of current feminism – a feminism that uses fashion as a tool to raise awareness and increase representation.’

The other broad-stroke highlight of the New Couture: Piccioli’s emergence as the genre’s current creative leader. He has assumed a more philosophical leadership role as well, working to change the exclusionary perception of couture with a message of inclusivity. As for his clothes, Piccioli has refined a glorious aesthetic at once romantic and current. His evening wear is extraordinary, with both subtle and sweeping statements. His daywear, on which he has recently increased focus, works sportswear concepts with an elevated sensibility that projects as haute but not arch.

Now there’s fresh competition in town, starting with Demna Gvasalia at Balenciaga. Gvasalia presented his first couture collection, and the house’s first since Cristóbal Balenciaga closed his shop in 1968. The fashion-hungry could hardly wait. Fold in the interest around two other recent haute arrivals – Roseberry, completing his second year at Schiaparelli, and Kim Jones, in his sophomore season at Fendi – and this season would have thrilled season under any circumstances. The long, Covid-wrought fashion drought only intensified the anticipatory thrall.

Gvasalia made a stunning debut. His audacity proved key to his selection as creative director of Balenciaga back in 2015. Since then, he has rocked fashion, inspiring endless knockoffs with his intense, sometimes aggressive and even dark perspective with an ever-present current of elevated street. Demonstrative in attitude and proportion, Gvasalia’s clothes are typically arresting but not particularly elegant – almost as if he has rejected elegance as antithetical to his purpose. Until now. For couture, he embraced haute elegance, mining the house archive for silhouette and detail, and also for mood; he showed in a silent, music-free atelier, just as Cristóbal had done. These clothes combined austerity and opulence, mid-century posture and modern savvy. Gvasalia flaunted impeccable tailoring in the series of chic black suits worn by women and men, and adeptness at the grand gesture – the guy can work bolts of taffeta into magic. And he kept a soupcon of street apparent in the haute allure. How else to describe the remarkable parka-Watteau gown hybrids? Clothes for dressing up, indeed.

Also shaking things up, Texas native Roseberry marked the completion of his second year at Schiaparelli with a high-impact collection. Like Gvasalia, he drew deliberately on the house roots. A stalwart provocateur, Elsa Schiaparelli brought surrealism to fashion and pioneered the concept of the artist collaboration, working most famously with Jean Cocteau and Salvador Dali, but also with, among others, Jean Dunand and Alberto Giacometti. Roseberry embraces Schiaparelli’s artful inclinations, particularly her penchant for trompe l’oeil and other surrealist turns. For autumn, he referenced her toreador looks while pushing the motif further in what he called ‘Matador Couture’.

‘I hope that I'm bringing some fearlessness back to couture,’ Roseberry says. ‘What I'm most surprised about is that I value bravery just as much as success. I want the collections to feel big, feel bold, feel like we are taking big swings and, hopefully, nailing it every season. I want to challenge couture, not to make it more streetwear or more accessible, but to make it more culturally relevant.’ Big and bold it was – from the aforementioned lung dress to the lavishly embroidered, sculptural jackets.

Jones took a more discreet approach at Fendi, while still working intense levels of craft into the clothes. By focusing on graceful shapes and a subdued palette against which he played elaborate embroideries and other treatments, he maintained a deliberate aura of serenity. Today’s couture, Jones says, should be ‘someone’s quiet personal luxury’ to which he seeks to bring ‘an English point of view’.

In fashion, point of view is paramount. Kerby Jean-Raymond became the first Black American designer to show on the official couture calendar – but not in Paris. He opted instead for Irvington, New York, and the grand residence built for Black hair-care entrepreneur Madam CJ Walker, the United States’ first female self-made millionaire. Jean-Raymond spotlighted social justice, opening his show with a passionate address by former Black Panther Party leader Elaine Brown and a different spin of the notion of dressing up, a series of playful costumes celebrating the accomplishments of Black inventors. Case in point: a model in a flowing yellow gown carried a white window frame inset with an air conditioner in homage to Frederick McKinley Jones, a self-taught engineer who invented a portable refrigeration process.

While Jean-Raymond made his first couture appearance, the house of Jean Paul Gaultier returned to the arena. It inaugurated its new guest-designer concept with Sacai’s Chitose Abe, who beautifully interpreted the founder’s rich iconography, both the items with which she has ample experience, including trench coat, plaids, military, and at least one new to her oeuvre, the cone bra.

Although newcomers garnered the lion’s share of attention, the season provided plenty of other points of interest. Giorgio Armani titled his Privé collection ‘Shine’, a name that presaged his lineup of exquisite evening looks in a luminous, deceptively potent palette. At Maison Margiela Artisanal, John Galliano produced a masterful film and collection. A Folk Horror Tale, directed by Olivier Dahan, spans two centuries, telling the tale of an insular fishing community afflicted by terrifying weather-induced mayhem. Iris van Herpen travelled skyward. Always pushing boundaries in her integration of technology and couture craft, for the collection she called ‘Earthrise’ she enlisted skydiver Domitille Kiger to take a plunge in an embroidered gown. The result mesmerised.

Elsewhere, Viktor & Rolf’s Viktor Horsting and Rolf Snoeren charmed and amused with their send-up of royal ways, Alexandre Vauthier celebrated Paris with a theatrical, mostly black collection, and Julie de Libran continued to develop her intimate approach, working when possible with existing materials. Then there was RVDK’s Ronald van der Kemp, who founded his house determined to craft high-style couture in an environmentally responsible way. He uses only existing, repurposed materials, here including chains, lamé and denim, which he wove and shredded into numerous marvels. ‘When you work only with what is already existing and not whatever you want, you have to find solutions. You’ve got to force yourself, push yourself, to create. This is what I love,’ Van de Kemp says. ‘It’s all made with love.’

Made with love, to wear with love. If ever there were a moment when fashion is good for psyche and soul, it’s now. Let’s dress up!