Tom Rasmussen discusses their new single ‘Fantasy Island Obsession’ ft. model and poet Kai-Isaiah Jamal.

In late March, Tom Rasmussen released their first single, ‘Fantasy Island Obsession’. A snappily pared back dance track, Tom shares the lead melody line dancing toe-to-toe with a muted trumpet. The non-binary poet, model and muse of the late Virgil Abloh, Kai-Isaiah Jamal introduces the record with an unedited voice-note taken from Tom’s phone. The song was inspired by a conversation the two friends once had while driving through South-West London in a transit van, about the proximity to death queer people must learn to navigate life.

In three repeated words, Tom manages to encapsulate the whole ‘Go West’ fantasia. There is a kind of maudlin euphoria to it, a happy/sad motif which manages to sound both perky and philosophic. Like Tom, ‘Fantasy Island Obsession’ wears its depths lightly. It makes brief and formidable work of announcing their sincere intentions to step away from the East End drag circuit which launched their public profile and enter the realm of pop performer. ‘Twas ever the dream.

I’ve always had a soft spot for Tom. They entered the East End nightlife 11 years ago, initially reminding me of a young Lily Savage, as if re-drawn through the 21st century queer lens. They initially foreshadowed then dovetailed with some big questions about gender a generation has needed to ask. As Crystal Rasmussen, occasionally Tom Glitter, Tom’s persona was always whip-smart funny, but it had a point, too. Their drag was Northern. It was working class. It revoked the binary politically and personally, not just as dress-up. It could not help but invoke the twin touchstones of Divine David Hoyle and a vintage Coronation Street barmaid. That automatically ticked a lot of boxes.

Yet it was when Tom broke out into song that you could feel something more layered at work in their arresting stage persona. Tom became one of the few working class Northern drag queens to sign a book deal with a serious publishing house. First with Diary of a Drag Queen, then First Came Love, they delved into their own modus operandi, asking tough questions in an accessible, literary manner.

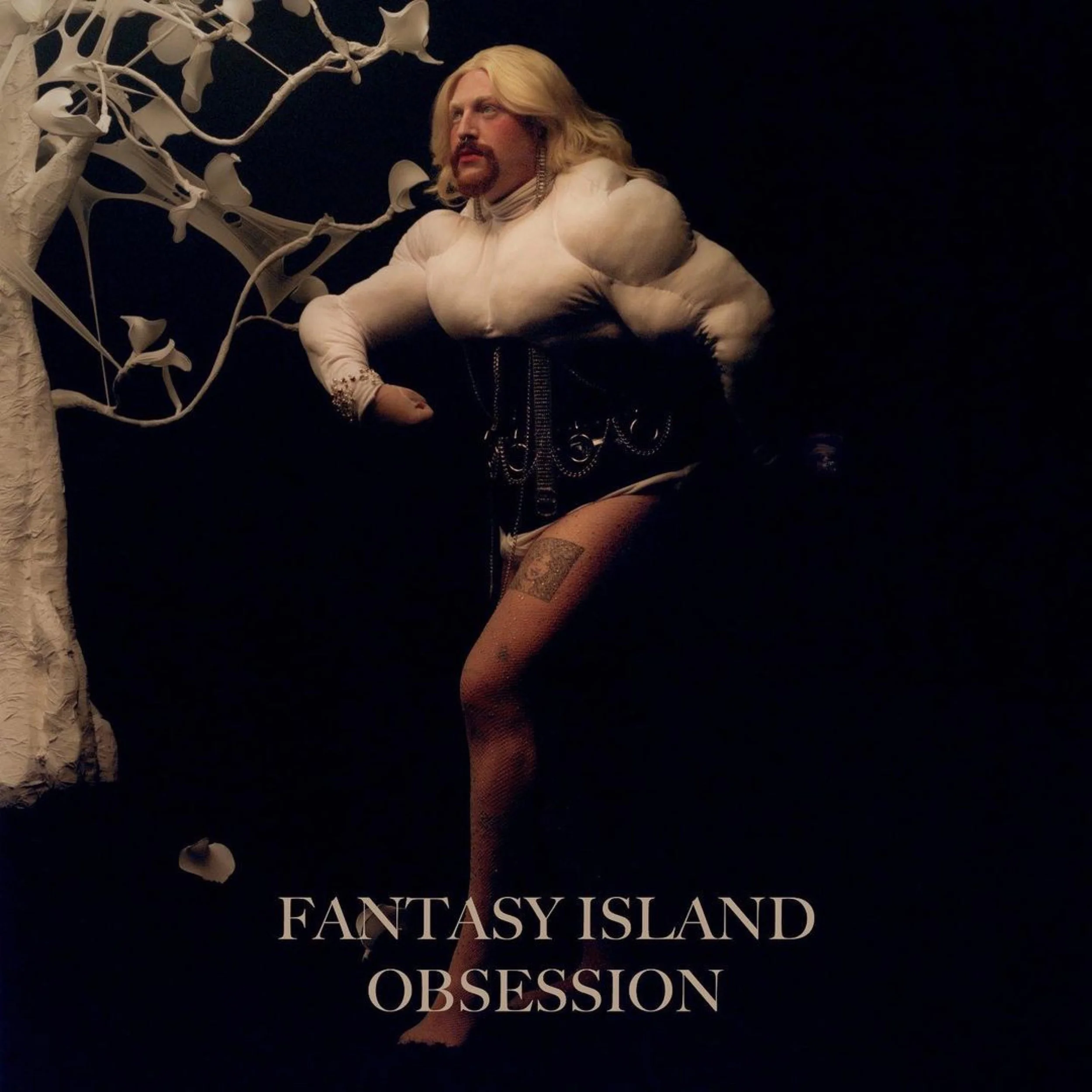

‘Fantasy Island Obsession’ is the perfect introductory vehicle for Tom’s pop life, drawn from noble, pure intentions. For the video, they wear a waist-length blonde wig, muscled bodysuit made by the Newcastle artist, Adam Wilson-Holmes (delightfully @straightbutcurious on Instagram) and a jewelled corset styled by Bojana Kozarevic, while rolling straight-faced around in the mud.

There is a metaphor buried in there somewhere, as Tom chops down a palm-tree and blood seeps from the trunk. As they enter the third phase of their career, just turned 30, it feels like the explaining is done. As pop star, Tom Rasmussen is determinedly show-don’t-tell. It suits them handsomely.

Paul Flynn: Where am I speaking to you?

Tom Rasmussen: I’m in Blackburn, in a hotel. I actually love it. It’s a budget Hilton. Cheap and chic. I’m doing the Take That film which I don’t know whether I can talk about but I haven’t signed anything, so. I like Blackburn. On special occasions I used to come to a really decrepit ice rink here. It was run by this woman called Molly who was fucking awful. I was absolutely obsessed with her.

Paul Flynn: What’s the music that reminds you of that ice rink?

Tom Rasmussen: Probably Whitney. They’d play these big emotional power ballads, then you’d come off the rink and she’d have made this huge shepherd’s pie. You’d be at some kid’s birthday party and there’d be ten of you and Molly’s massive shepherd’s pie. “You gonna finish it?”

Paul Flynn: How’s your part panning out?

Tom Rasmussen: I’m a bus driver for two scenes. He’s a fucking bastard, then he turns into a drag queen. It’s one of those classics. All to Relight My Fire.

Paul Flynn: Very 2022. Welcome to the bridge over the culture war.

Tom Rasmussen: Oh my god, stop. That’s me.

Paul Flynn: At what age did the persona of Tom Glitter: Pop Star begin germinating?

Tom Rasmussen: Well, ‘Tom Glitter’ is unfortunately just a handle that I wish I could leave behind. I was 15 and we were doing our IT coursework at school. Mine was going off to be moderated by examiners and my friend said, “I dare you to put a stupid name on.” So, I put Tom Keith Glitter Sky Rasmussen on every page. Tom Glitter. Then it was my Facebook name, which was actually Tom Glitter McGlitterson. It was a piss-take. I was sending my own very bawdy sexuality up before anyone else could. I was up north, in Lancaster, at a Catholic state school. I had a great time, amazing friends but it was also very homophobic. I’ve written a lot about growing up and you can find yourself writing yourself into certain corners. So, the persona of Tom Glitter, if I’m being completely honest with you, is over. I was 30 last year and I’ve wanted to be a singer, a proper singer that writes my own music forever.

Paul Flynn: I remember seeing you at The Vauxhall Tavern and you breaking out into Kylie’s ‘Confide In Me’. It was the week she was playing Glastonbury and it sounded, really quite beautiful. Are you classically trained?

Tom Rasmussen: No, I only started singing lessons last year, in lockdown. I was obsessed with female singers. The only thing I can really remember from puberty was about my voice, feeling like I was losing that ability to sing high. So, I kept on singing to Celine Dion and it never stopped being high. I have this theory that it’s another way that gender is quite performed. All of a sudden all the boys are like [comically low voice] “yeah, I talk like this now.” And it’s kind of not. But anyway. Pop star me? I’ve done so many things in my twenties that I’ve been so lucky to do, worked with so many cool people in culture and fashion. I’ve written books, sung at the Opera House in drag, played Glastonbury, all this stuff that I never thought I’d be able to do. All of that stuff was really wonderful, such a privilege but none of it was this: writing and releasing music of my own. I’m glad I didn’t have as much clarity when I was younger. I’m glad I didn’t know that someone like me – a working class queer person from up north – could do. In a way, the first thing I had to do was make money. I’m glad it’s now.

Paul Flynn: You emerged into a time that was flooded with reality TV, when pop stardom was that strange lottery where you’re either Leona Lewis or Rylan.

Tom Rasmussen: I mean, love those two.

Paul Flynn: Then the Drag Race behemoth arrives.

Tom Rasmussen: With drag, I had got to the point where the only options were quit or do reality TV. I think a lot about this. Growing up queer or gay or trans, half the people would say horrible shit, “die faggot” vibes. The other half would say, “oh, you’re so going to be famous.” That becomes this weird new binary. If I don’t want to stay in the terrible place, I have to step into this sort of absurd character, the amplified version of being queer. During my entire twenties there was this awful feeling that if I’m not famous, or not known for being fun, loud and fabulous, then what am I? Do I wither and die? Queer people are pushed into this strange position of fabulous or failure. There are very few routes to that. There’s terrible music or reality TV. Drag is fucking hard work. The money’s shit, the nights are long, the violence is high and people are fucking knackered. I don’t know how this pans out. [During lockdowns] I sat for two years feeling weirdly jealous, bitter and sad that something that felt so liberating was ending. Then also curious. Did I want to do it? No, what I really fucking want to do is write and record music.

Paul Flynn: That’s such a great observation about gay adolescence being a paradigm between fabulous and failure. They’re odd extremes to hold in your head simultaneously, the star-studded amazing version of yourself and the weeping wreck on the street.

Tom Rasmussen: Right? But also, this is the problem and the wonder of being queer. That failure option sounds more glamorous to me than something like normality. I guess normality to me always felt like death. And normality to me is suburban, lower middle-class, same thing every day. It was obscurity or fame and I don’t feel that anymore, which I think is why I was able to write something that I’m really proud of.

Paul Flynn: You were very careful to thread your class through your portfolio from the start, the one diversity and inclusion issue every corporation currently ticking boxes tends to conveniently forget.

Tom Rasmussen: They all say it’s kind of over. And it’s so not. Don’t be so fucking stupid.

Paul Flynn: Who was the first pop star you were obsessed with as a child?

Tom Rasmussen: Madonna.

Paul Flynn: What was your Madonna entry point?

Tom Rasmussen: ‘Ray of Light’. I was 8. I didn’t understand it. But I loved it.

Paul Flynn: You didn’t know what a zephyr was?

Tom Rasmussen: I still don’t, bitch. But I loved it. A friend of mine’s mum had it and we were obsessed. Obsessed with the video for ‘Frozen’. I mean, who isn’t? Then properly got re-obsessed at ‘Confessions…’, which is what? 2004?

Paul Flynn: By now you’re 14, 15 and I imagine this is the first Madonna record you ever experience drunk, a whole revelatory rite of passage in itself.

Tom Rasmussen: Yes, we saved up enough money and went to the ‘Confessions’ tour where I got punched in the face. It was me and this incredible Butch vying for the front row. You know what it’s like at a Madonna concert. Especially then. Me and this woman were just vying for the front and she honestly just smacked me in the eye. She got dragged out by security and I got my place on the front row. It was incredible. I’m not saying I deserved it but, back then I was quite happy to receive violence from a Madonna fan. It was actually the opposite of homophobic. It was super gay. Fighting for our right to stand in front of Madonna.

Paul Flynn: What did Madonna represent to you?

Tom Rasmussen: I don’t know if anyone’s managed to reach the absolute mass while still being so punk as she was. It’s unbelievable. It’s a shame because I don’t know whether that could happen again today.

Paul Flynn: Will there be a full album to follow ‘Fantasy Island Obsession'?

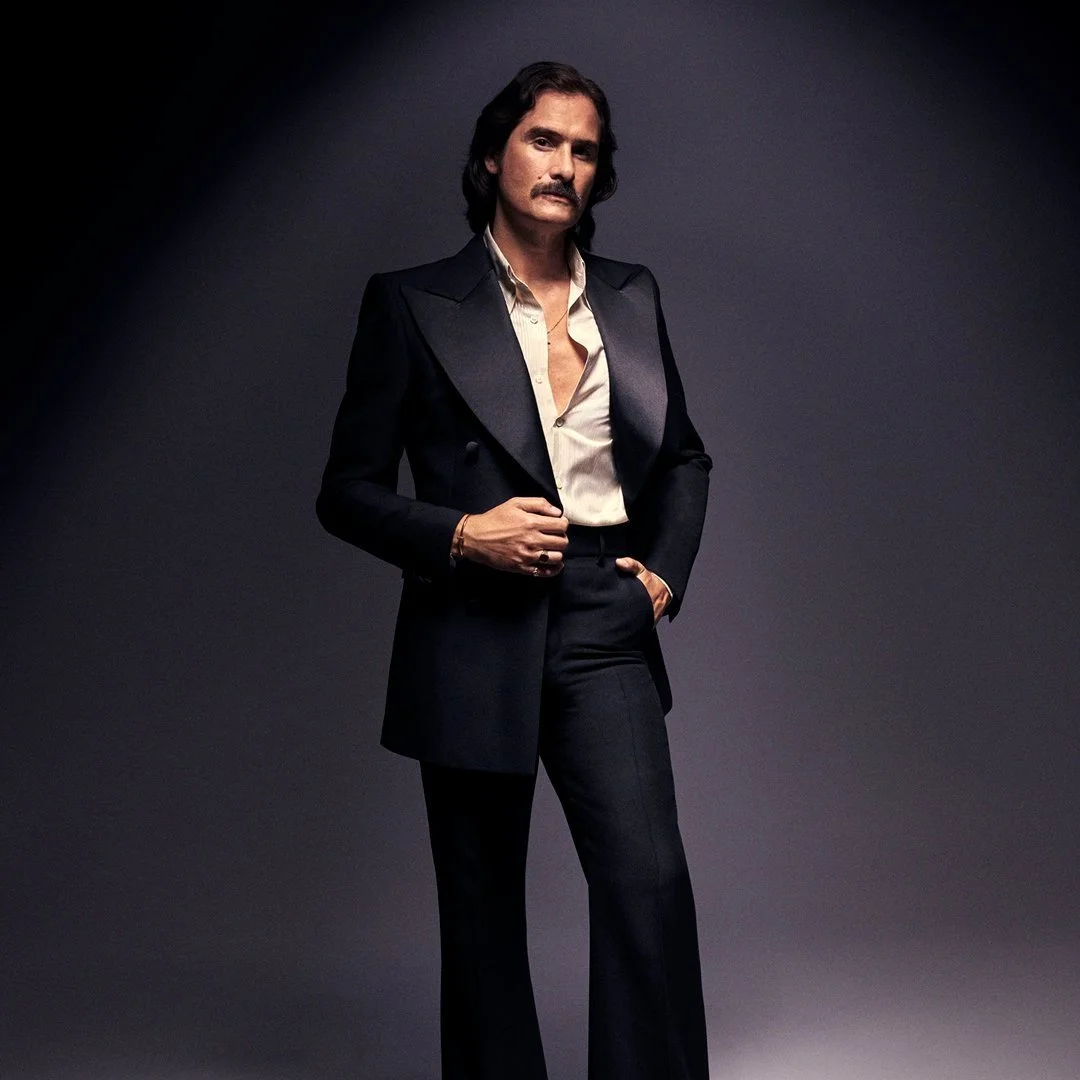

Tom Rasmussen: Yes. Tim Walker just shot the cover, which is very exciting. There wasn’t ever a moment where someone said to me this is too freaky, or not the right genre. It’s just been support. The general idea of the album is violence in three acts. There’s a lot I worked with in my twenties that I feel ready to leave behind. Experiencing a lot of violence, especially in the early years of my twenties when I would run around the streets of East London in high heels and ballgowns. All the way through high school, too. It’s the classic story of getting beaten up, a lot, finding a powerful community and then almost writing about that violence as a means to feel seen but, also as a means to get paid. It’s a strange dynamic. There was a thing John Waters said, “I went to the gay club and realised I wanted to be Bohemian, not gay.” That’s not me. I love being gay, being queer, being non-binary and trans. But at the same time, I guess the record is about trying to find something outside of those spaces. I came of age in the era of identity politics. I really believed in the transformative power of visibility. Yet nothing’s changed.

Paul Flynn: Every generation thinks that they will be the ones to change everything, but being a minority is always primarily negotiating being that minority.

Tom Rasmussen: Yep.

Paul Flynn: We know what it feels like to be used as a tool to deflect against the serious issues of the day. We saw it yesterday, Boris Johnson deliberately bringing up the trans in sport debate to deflect from his disastrous handling of the money people have in their pockets during a cost of living crisis. You can set your clock by this stuff.

Tom Rasmussen: Right?

Paul Flynn: Because that’s what the waitresses serving you in the budget Hilton, Blackburn care about.

Tom Rasmussen: Yeah.

Paul Flynn: How qualified is our Prime Minister to make that statement about trans people?

Tom Rasmussen: You absolutely know the answer to this. He’s unqualified to do fucking anything, let alone be qualified to fucking comment on that. It is all deflection from the fact that they’re responsible for literally murdering poor people. That’s what this party does. It’s mass murder. No-one says it. Let’s not, because I… [trails off]

Paul Flynn: There was a lot of interesting things about your emergence but what I particularly loved about you and your group of friends when you all appeared was that you were funny, yes, culturally literate, yes, 100% queer, yes, but you were also clever. The first thing you did in the mainstream was sign book deals. That’s amazing.

Tom Rasmussen: [laughs] I know! But I still got no bloody money. But yeah, it was. You’re right. That was amazing.

Paul Flynn: You wrote literature, then you made pop music. It almost untangles the pop myth in reverse.

Tom Rasmussen: To me, it’s all constantly honing the act of writing. What I love about writing books is that I don’t feel lonely. I’m thinking about something all the time that isn’t… loneliness. And also, you have loads of time to explain yourself. This first song, ‘Fantasy Island Obsession’ is three words. I was thinking so much about repeat phrases. It’s got to be specific enough for it to feel personal to the artist, but also broad and un-specific enough to appeal outside of that. Why do I understand ‘Substitute for Love’ by Madonna. That’s about Madonna being fed up with fame and having a child and finding truth and meaning. But I’m obsessed with that song.

Paul Flynn: That and ‘Into The Groove’ are my favourite Madonna songs.

Tom Rasmussen: ‘Into the Groove’?

Paul Flynn: It was for me what Hung Up was for you, my first drunk Madonna song, when I was 14. I saw Desperately Seeking Susan at the Odeon in Manchester and it was the same week the first McDonalds opened in the city so I tasted my first Big Mac and heard ‘Into The Groove’ on a big sound system for the first time on the same day.

Tom Rasmussen: Oh, that makes me want to cry. Honestly, that is the stuff that dreams are made of. Cerebral pursuits, though. A really cerebral and interesting friend of mine said, on her 30th birthday a few weeks ago that it’s so interesting that we will never be the voice of youth again. I mean, none of us ever were, obviously. But in a way, thank God. Because some of the shit I wrote. Some of the shit I thought. Plain stupid. But that’s the learning process of so many generations.

Paul Flynn: But yours documented it all. You laid it all out, gave it to everyone. The primary methods of communication had turned from one-to-one to one-to-mass.

Tom Rasmussen: I’m 30 and I’m only learning about privacy now, for the first time. It also plays into that fabulous or failure thing. I got into writing articles for £150 that really mined my trauma. I got lucky and I learned a lot from that. But it is not a healthy way to do it. I started therapy two years ago and had a year-long, complete psychological transformation. This album is about all those things. At this point, and maybe I’m really privileged to say this, but I’m just trying to search for what is meaningful. I still don’t know. Relationships. How you treat the people in your real life.

Paul Flynn: Tellingly, you wrote your second book, First Came Love about romance. What did it teach you?

Tom Rasmussen: It taught me that you can’t be morally pure, weirdly. I have been so self-punishing about being morally impure. My obsession with marriage but hatred of the patriarchy. What do you do with that? How do you proceed in life? So, it taught me that no-one cares, love is really important, you can’t be morally pure and it’s OK to be a bit messy. It’s OK to make a mistake, to learn.

Paul Flynn: What do you mean by moral purity, Tom?

Tom Rasmussen: I think it’s to have a constant alignment of your intellectual life with your emotional feeling.

And that’s not possible.

Paul Flynn: Wow, you’re good. That’s a very wise lesson to have learned by 30. When you peel a layer away from you there is a very serious, deep-thinking individual. I sometimes think for queer people, there is a kind of moral purity in just allowing that person to exist.

Tom Rasmussen: Well, precisely.

Paul Flynn: You realise that Tim shooting your album means you have the same debut cover photographer as Harry Styles?

Tom Rasmussen: Oh my god. I’m going death and flesh though.

Paul Flynn: What’s the importance of Kai’s guest appearance on ‘Fantasy Island Obsession’?

Tom Rasmussen: We’ve been friends for years. We first met during a work reading panel in Hackney. It was before Kai even had Instagram and we fell in love straight away, in a platonic way. They moved out of one of the places they were living in, and we were driving round in a transit van all day with a table from Putney they’d bought from Facebook marketplace. We got out of the car in Putney, pure idyllic middle-class suburbia. Someone shouted something out at us and Kai and I got into this spiral about how trans people, especially of colour live in much closer proximity to death all the time. It’s something you have to consider. As a gay person, trans person, person of colour, your proximity to death is closer than the family that we were picking up the table from. Then we were talking loads about what it would be like if there was a place where only people who understood that were together. I went into the studio and wrote the song, ‘Fantasy Island Obsession’. I told them and Kai sent me this voice-note back about what their island would look like and that’s what’s on the record. It was all dreamed up in a transit van. Two trans in a transit van.

Paul Flynn: I’ll let you get back to being a bus-driver. What’s your costume like?

Tom Rasmussen: I look like a serial killer. Which I don’t find un-hot. I sent a picture to my boyfriend and he sent a nude back. So, it’s working.