Emily Ratajkowski.

A man waved a cardboard sheet across a lamp to make it seem as though Emily Ratajkowski and I were watching a film, with light from a moving image flickering on our faces. The screen in front of us was empty, a blank and silver wall.

‘Where are you looking?’ she asked me to ensure our lines of sight would be coordinated in the final image.

‘In the middle, right above that stand.’

Under the screen, a team of photographers, videographers, stylists, and hair and make-up artists prepared to shoot. Standing at the entrance was a guard and courier assigned to the expensive necklace that adorned my collarbone. It could touch me, but I could not touch it – there was a designated handler to fasten and unfasten the clasp.

The following month, Ratajkowski and I spoke again and I asked her what, if anything, she imagined was playing on the screen while we were being recorded.

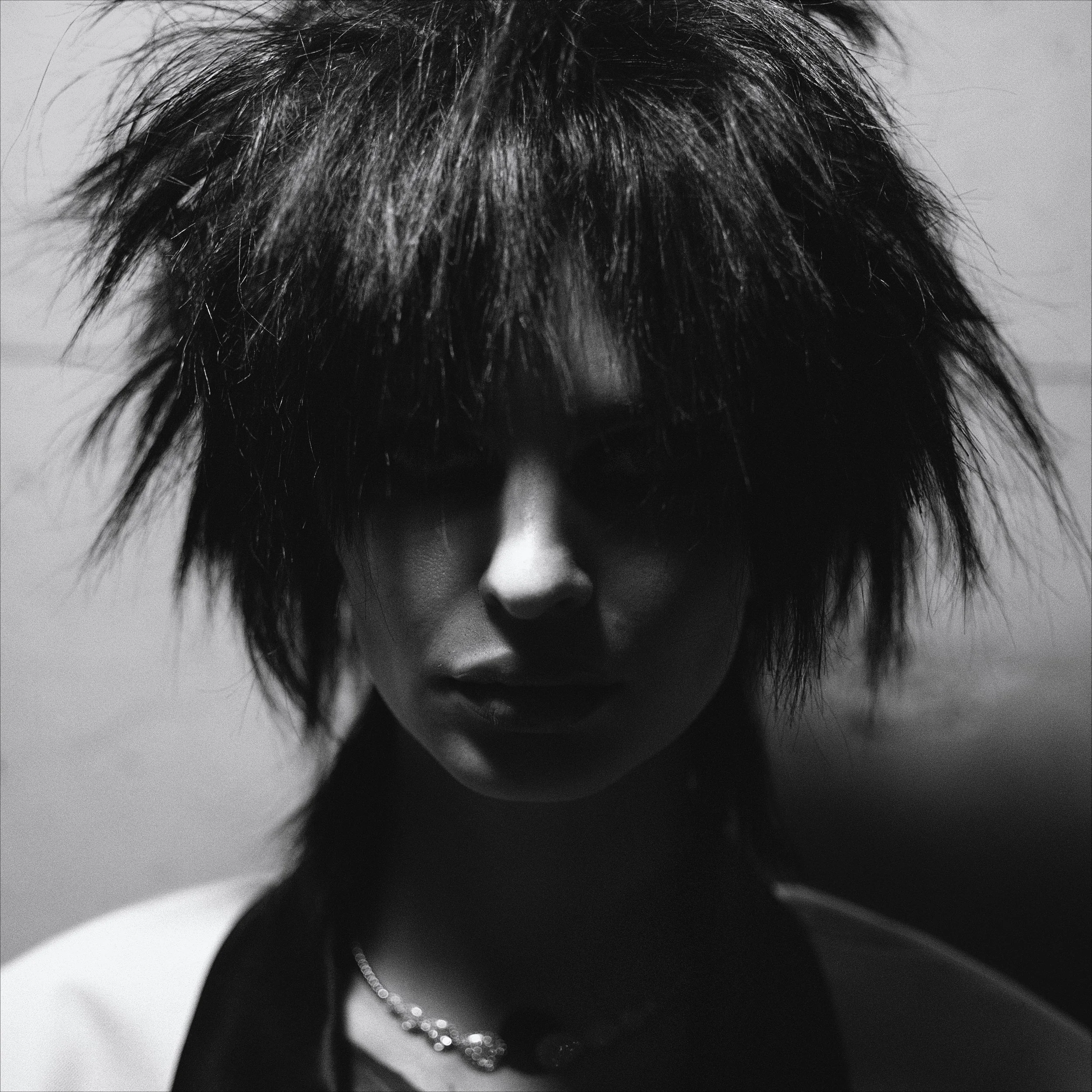

‘Right before you’d gotten there we had been playing the film we shot that morning. The idea was that my character was a performance artist and that she had made a film.’ There is overlap here with the real Ratajkowski; as an undergrad studying art at UCLA, she made performances and films about ‘self and objectification and power’, the same themes as those explored in her new essay collection, My Body. ‘In my mind it was like some alternate existence, that character I had taken on in the shoot, who had gone to art school but had a very different life. But she was still thinking about the same things. So initially I was imagining that.’

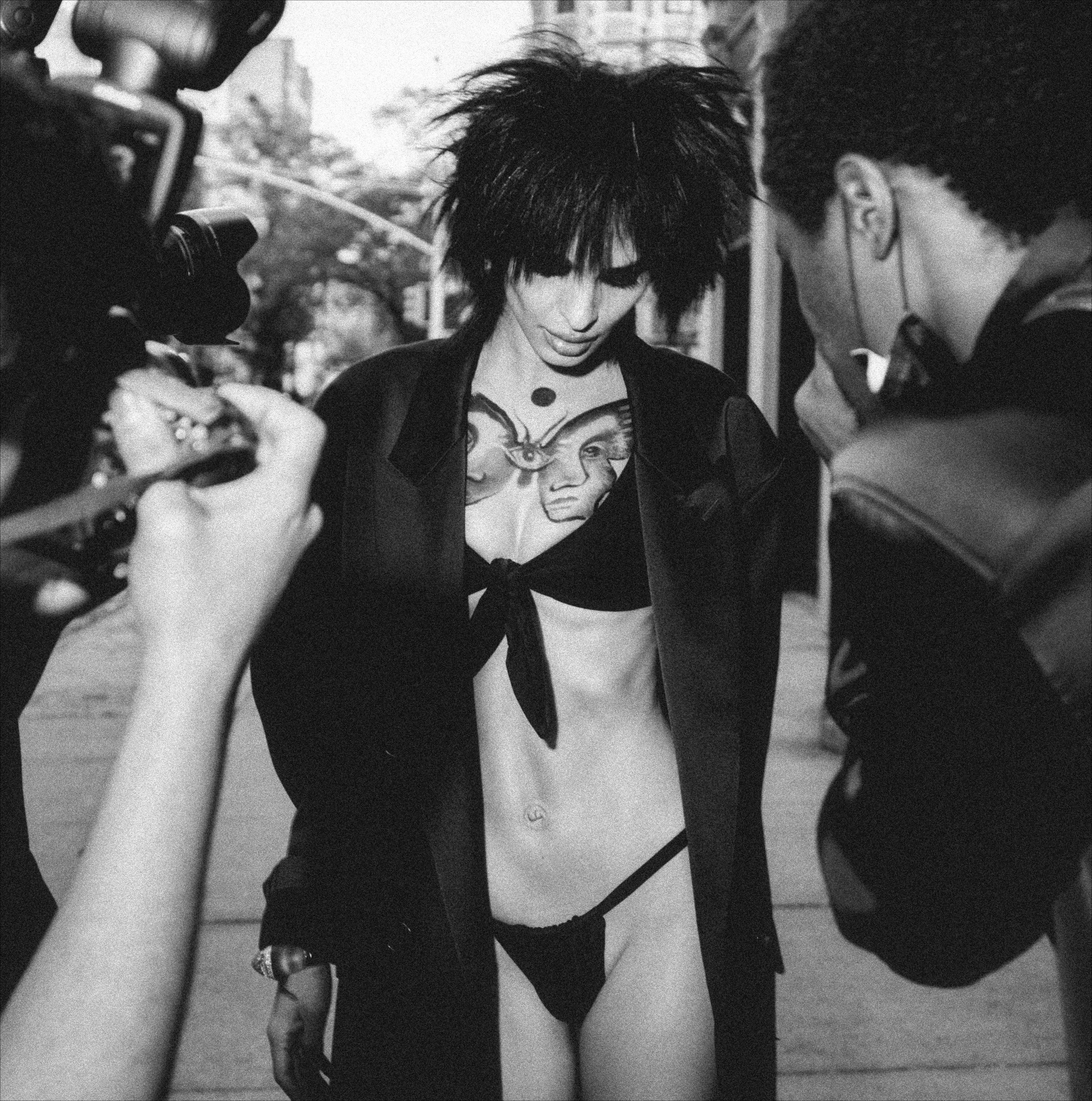

Alternate existences, parallel-but-not-identical lives, are not unfamiliar to Ratajkowski. As a model, she learned to adopt a distinct on-set persona as a protective measure to keep her work and personal identities separate. Early on in her career, she found safety in drawing a Cartesian line between ‘the modelling, physical Emily, and the “other” Emily’, the Emily that was seen and the Emily that saw. Modelling required ‘hyper self-awareness’, and ‘partly from becoming so physically aware of [her] body from other people’s perspectives’, she quickly realised discrepancies between how she saw herself and how others saw her. ‘When I think of my actual personhood, it doesn’t feel physical at all.”

The title My Body is partially a reference to a work of art by the writer and artist Hannah Black titled My Bodies, which Ratajkowski describes as ‘beautiful and haunting – a weird mixtape.’ In My Bodies, recordings of Black female musicians saying or singing the phrase ‘my body’ are stitched together in a single audio file that plays over images of white men before turning into a short parable about reincarnation. Black told Artforum that My Bodies is ‘partly a critique of the white-feminist conception of the body, the heritage from the Sixties and Seventies which involves the affirmation of white nudity, displaying the agency of white naked bodies’. In her essays, Ratajkowski expresses skepticism toward the way nude images of her, a white, cis woman, have been endowed with a politic or ideology that doesn’t reflect reality, in media narratives of both victimhood and empowerment, if not both.

When she first viewed My Bodies, the piece caused Ratajkowski to reflect on how women who are perceived as powerful in society often articulate that power by invoking their bodies, and the relationship between the celebrity personae of these women and their lived, material experiences. A pop star’s interaction with her fans is predominantly virtual and impersonal, but her incorporeal persona is still rooted in flesh, in the face on her album art and the vocal cords that produce the words ‘my body’.

One way of thinking about Black’s piece relies on the phenomenon of semantic satiation, wherein repetition of a word or phrase erodes its meaning until it is reduced to nonsense. Hearing Beyoncé or Rihanna say ‘my body’, it is easy to imagine what the famous singers look like, but as the phrase repeats, one’s ability to connect it to anything visual slides away. The words ‘my body’ become immaterial, a sound, without appearance, without weight. In interviews, Ratajkowski often returns to a point about how difficult it is for her to tell whether any given image of her is ‘good’ or ‘bad.’ In her book, she writes about ‘how I dissociate when my body is being observed, how I don’t even really recognise my body as me’. Perhaps, like with hearing a word over and over and over again, this is the inevitable outcome of being exposed to your own image so many times.

Few relate to having their photographs circulated as widely as Ratajkowski, but she makes a strong case that this experience of dissociation and self-objectification has become a common feature of many people’s daily lives. ‘We’re all taking so many images of ourselves. It’s kind of a manic, thoughtless thing that we do now. You don’t have to be a celebrity to think about what kind of image you’re putting out online.’ In the essay ‘K-Spa’, she writes about finding comfort and freedom in the uniformity of the routine that clients go through at a public bathhouse, where she has never been recognised, ‘or at least no one has ever made it known that they recognize me’.

For someone so used to being singled out, anonymity has transformed into a delicate pleasure. Living in Manhattan – where crowds of faces, recognisable and unknown alike, blend together in a madcap collage – allows her to feel less alienated from her environment. On a morning walk to her office, she described to me ‘a moment of feeling one of many, like a part of something while also not being singled out or special in any way. I really treasure that about living here.’ I fumbled to recall a line from Tolstoy’s The Kreutzer Sonata in response: ‘In the city… one can live a hundred years without being noticed.’ ‘Right after our shoot,’ she told me, ‘I went and saw a movie by myself. I put on a big hat and a mask and sat in a row with a lot of people and ate sour patch straws and had a diet coke.”

Ratajkowski is not naive about her status as a celebrity, and she is not trying to affect the cliché of a star who longs to disavow both the curse and benediction of fame. Rather, her interest lies in showing how the trappings of her role are the same that many people, especially women, contend with on a daily basis. A common example she returns to is that of doctor-patient relationships, wherein patients are forced to cede control over their bodies and allow them to be assessed, submitting to doctors like cars to a mechanic. While pregnant, Ratajkowski visited doctors often and found herself in the complicated situation of ‘needing them but also resenting their help, and realising it wasn't just the objectification, it was the idea they felt they knew my body better than me and felt some ownership or authority over it’. In an essay titled ‘The Woozies,’ Ratajkowski accompanies her mother to the doctor for a consultation regarding her mother’s amyloidosis diagnosis. The doctor, checking for symptoms in her eyes, asks if she is wearing make-up. ‘Not eyeshadow, just some mascara,’ she responds. Emily stifles a sob while imagining her mother applying mascara in the mirror earlier that day. By linking her welling tears directly to the scene of her mother getting ready in front of a mirror, Ratajkowski reveals a subtle and discomfiting truth about the world via her mother’s unspoken fear that if doctors didn’t want to look at her body, then they wouldn’t want to save it.

Daily preparation and its accompanying rituals, the scene of a woman preparing herself in the mirror, fascinates Ratajkowski. One essay idea that didn’t make it into the book explored the performative aspects of putting together an outfit in the morning and ‘the decision-making process for a woman in deciding how you want to represent your body on a day to day basis’. We discussed how in addition to a personal clothing and visual style, a person’s favourite idioms, words and patterns of speech are also performative elements of identity formation. I asked what her literary influences were in developing her straightforward yet nuanced writing voice.

‘I like direct, clean, unpretentious writing. When I couldn’t find my voice, I would read bell hooks. Any idea that felt too difficult to write, she still tackled it in a simple way, and that gave me confidence. Lorrie Moore. Rebecca Solnit. Carmen Maria Machado…’ Ratajkowski’s style is accessible without resorting to platitudes, searching without landing on didacticism. She writes in order to understand herself, and has a genuine desire for the reader to understand along with her. ‘What happens is the first thing I write about is an experience and I don't understand why I wrote about the experience. Then I revisit it and realise why I’m drawn to that experience and felt a need to write about it, and expand on the idea.’ Every essay has its source in introspection, and it’s this sincere desire to embark on a journey inward and honestly record her findings that place the collection in a more literary echelon than most books labeled under the wide umbrella of ‘celebrity memoir’. She’s not a self-help guru, and she doesn’t profess to have any greater enlightenment or rarified knowledge than the reader. All she claims authority over are her own memories, and even those she refuses to accept at face value.

In the third essay, ‘My Son, Sun’, Ratajkowski recounts a high-school relationship with a manipulative and abusive boyfriend. One night he visited her home in tears and it became her responsibility to console him: ‘My parents stayed inside and out of sight. It seemed as if everyone understood the role I was supposed to play. I inhaled and drew up a memory of how I thought a woman behaved when she comforted a man. Maybe it was a moment from a movie? I wasn’t sure.’ The scene is an eerie illustration of how gender roles are ambiently disseminated through both family and mass culture, where the messaging is so insistent and frequent that it becomes difficult to trace with much specificity. Present day, Ratajkowski herself has become a widely known point of reference for many people’s conceptions of femininity. ‘One of the reasons I wrote this book – there are many – was considering what people are used to seeing of me online and what I can represent in media, and feeling frustrated with my inability to paint a fuller picture.’ It’s important to her that her legacy speaks to a more complex and full personhood than is revealed in most photoshoots, but she is not trying to win over anyone’s respect and approval. Just like we all do in the mirror each morning, Ratajkowski makes decisions on how to represent herself to the world based on a mix of intuition and personal desire. ‘I can only answer to myself and what feels good to me and what ultimately makes me feel in control and true to myself.’

Today, a barrier between Ratajkowski’s physical and mental selves is less of a crucial shield than when she first began modelling at the age of 14. She told me she is finally settling into a sense of alignment and unity between all her varied existences. And in addition to movie theatres and Manhattan streets and Korean spas, she has discovered a deeper location of anonymous communality: motherhood. ‘Becoming a mother is special, but it’s also such a normal position to be in,’ she says. Even though there is something singular about becoming her infant child’s entire world, it’s incomparable to the other ‘bullshit specialness’ associated with the American cult of celebrity. Being someone’s mother is common in spite of it denoting a particular, personal relationship between two people; it’s the inverse of fame, which is uncommon yet denotes a general, impersonal relationship between one and many. Childbirth and other life experiences have recently granted Ratajkowski ‘a new appreciation and a new ability to be in my body and feel like myself’.

Although Ratajkowski writes about art, family, health, sex and more with equal clarity, many readers are still fixated on her career as a model, perhaps because that is the Emily they are most familiar with or most desire to see. I admit that it was Ratjkowski’s writing specifically about modelling that first sparked my interest in reading her. Her words helped me contextualise and explain some of my own experiences working as a model, albeit in a more limited capacity than Ratajkowski. It’s rare that someone who has worked as a professional model attempts to articulate the nature of the profession with true curiosity and incision, and I am grateful for her contribution.

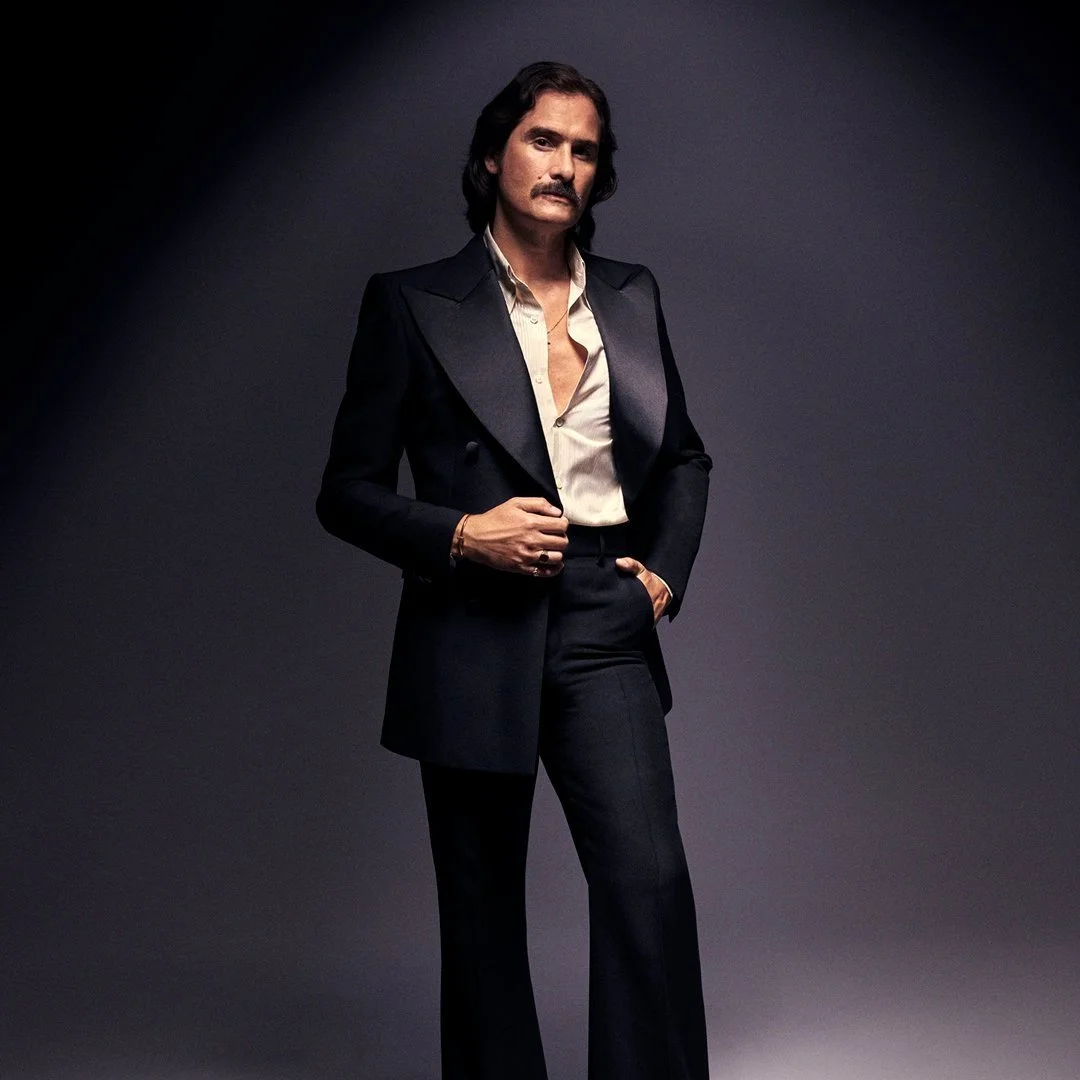

I’m slow to ascribe any particular skill or valour to modelling, knowing that success is largely determined by the lottery of birth. However, I do believe there are varying degrees of talent and professionalism among models, and working alongside Ratajkowski affirmed this notion. I was impressed by how quickly and effortlessly she adapted her body to the needs of a particular shot, her poses intuitive and unbidden. Her question to me about the angle of my gaze revealed foresight and attention to detail, and her affability ensured a smooth production.

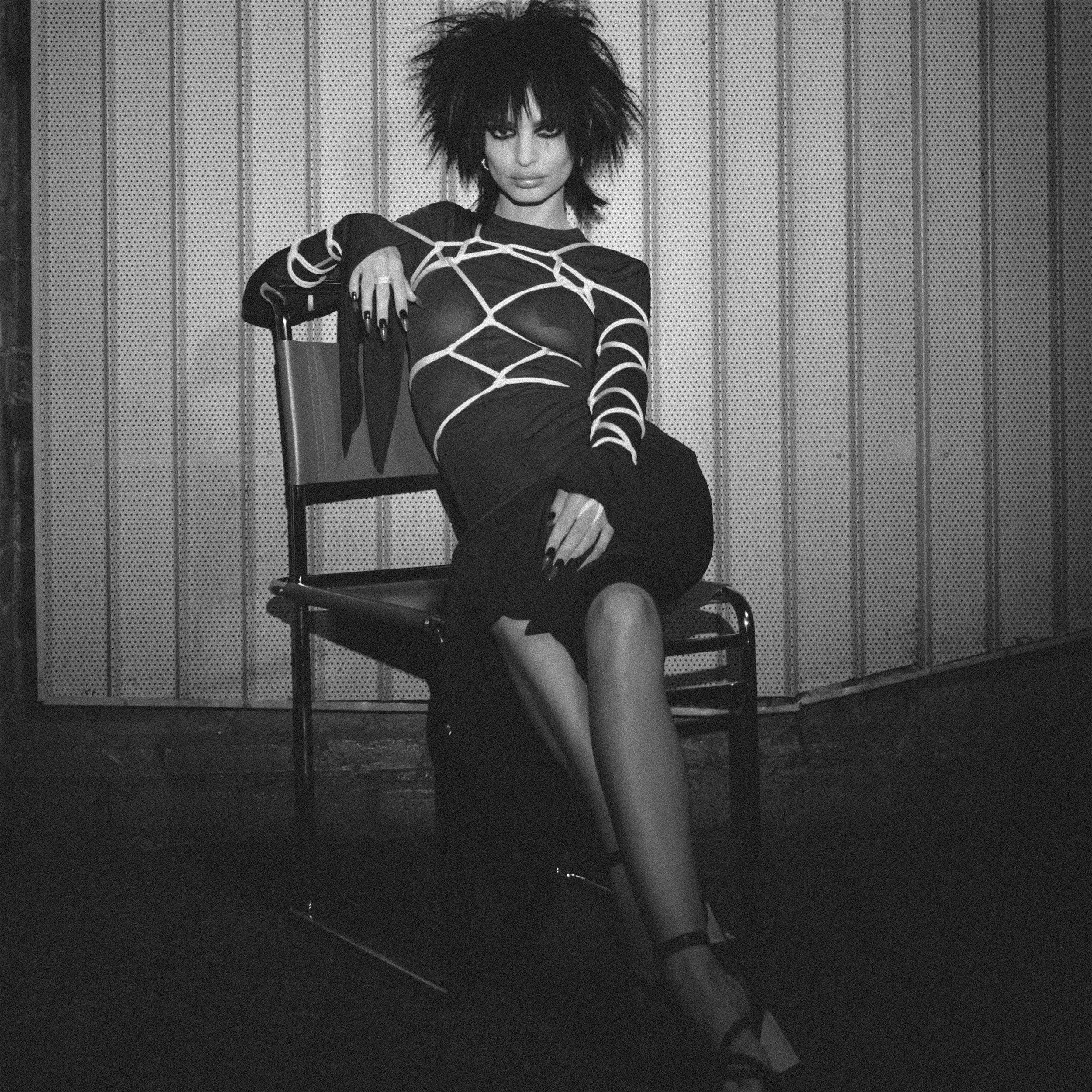

When the credits rolled on our imaginary movie, it was time for solo shots. I joined the crew while Ratajkowski took control of the scene. Alone in a sea of red velvet, we watched her watch the empty screen just above our heads. Sitting in the audience, she remained a star.