Fame.

Last November, Gucci shut down Hollywood Boulevard to present its spring 2022 collection in a show both modelled and attended by an endless list of A-list celebrities. Staged at the heart of the myth-making industry, what light did this parade of familiar yet unknowable legends cast on the subject of contemporary fame?

Fame is a state of existence wherein you are recognised by more people than you recognise. Many more, though it’s difficult to give an exact amount. It’s being approached by expectant strangers who already know your name, like in a dream. It’s the power to command an audience’s desires, to influence what they want to be and how they want to live, even if you only inspire them to be the opposite of whatever example you set forth. Contempt is as influential as adoration. In the eyes of others, mortals are magnified to the size of gods, and a celebrity is someone whose name or image fills the eyes of millions every day.

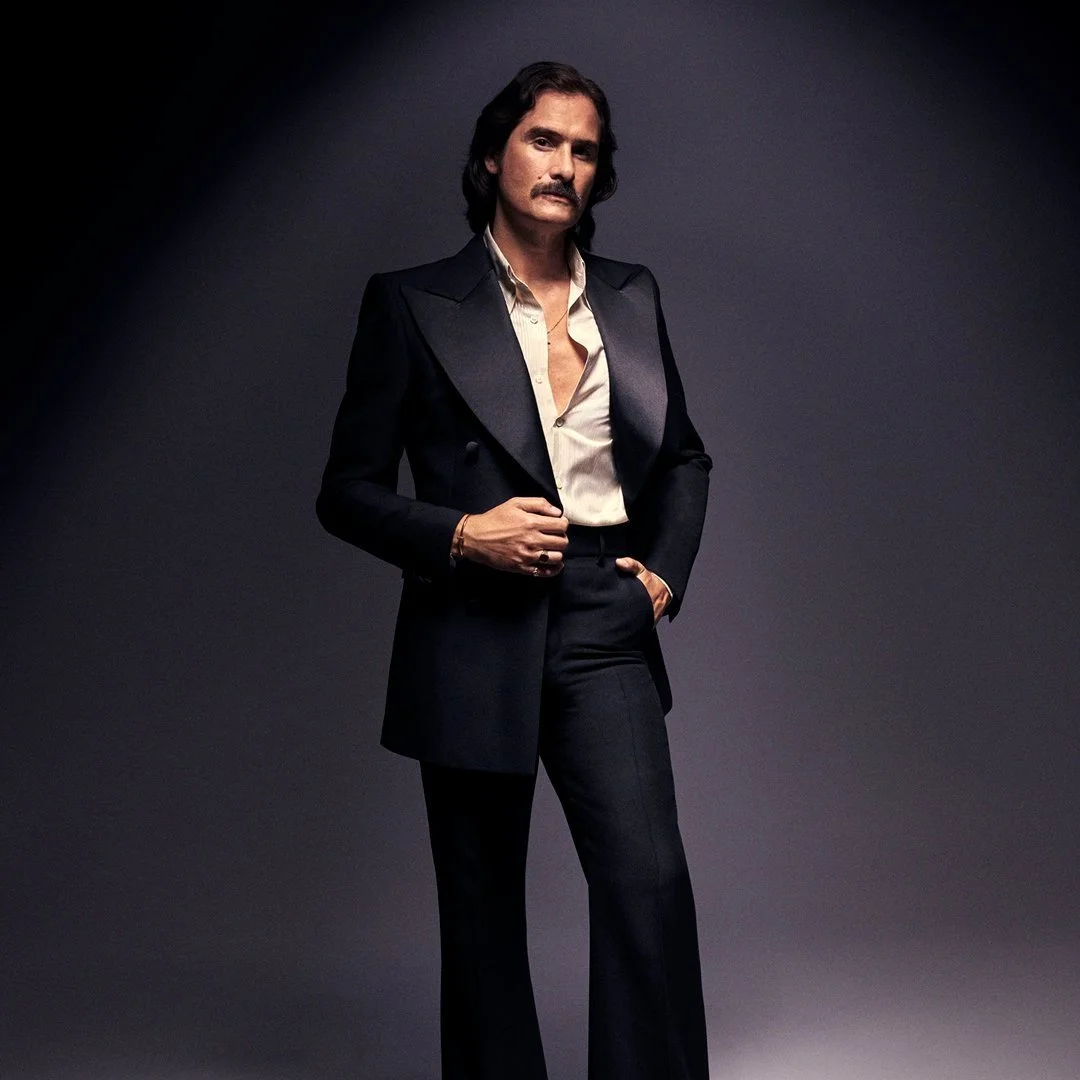

In his show notes for last November’s Gucci Love Parade on Hollywood Boulevard, designer Alessandro Michele wrote: ‘Hollywood is, after all, a Greek temple populated by pagan divinities. Actors and actresses are hybrid creatures with the power to hold divine transcendence and mortal existence at the same time, both the imaginary and the real. Beyond reach, and yet, so human.’ If the Boulevard was religious architecture, then the Love Parade was its grand ceremony, its Saturnalia or Easter. Divinities Billie Eilish, Tyler the Creator, Diane Keaton, Lizzo and more were in the audience, while Phoebe Bridgers, Macaulay Culkin and Jodie Turner-Smith walked the runway as models. As a threshold between fantasy and reality, celebrities offer people a living model of their imaginations. What are beautiful clothes without beautiful people to wear them?

At the show, Gwyneth Paltrow was dressed in an updated version of the iconic red velvet suit designed by Tom Ford that she first wore to the VMAs in 1996. What makes the look so famous? Credit goes as much to Ford and Paltrow as the context. The red velvet of the carpet that Paltrow wore it on is as much a part of the story as the red velvet of the jacket itself. In order to infuse an item with desire, there needs to be scenarios, characters, events. What is perfume without a room to announce yourself in via scent, before heads have turned and seen your graceful visage? What is a vintage fur coat without a snowy Paris avenue to walk down while wearing it? What is lipstick without a lover’s mouth to leave traces of it on?

Hollywood creates its own set of myths, its own holy texts, through self-referential iconography. These myths serve as maps to contextualise and orient our lives in reference to, either towards or away from the narratives they offer. Like Athena and wisdom, Ares and war, Aphrodite and love, celebrities come to represent specific qualities and ideals rather than complete selves. Teenage pop stars are treated as universal avatars of youth. Athletes become the living embodiments of strength and health. Actors are associated with the characters they perform on screen. And so fans become attached to their favourite celebrities like they would become attached to ideals. The attachment a fan feels to a celebrity is not like the attachment they might feel to a friend in real life, but it may be even more fanatical, because, as an expression of ideals, it resembles attachments to religious teachings, political ideologies and romantic fantasies. People are willing to go a long way to protect what they imagine. Some are even willing to risk their lives to sustain a fantasy, preferring death over a life with no spirit, no love, no meaning.

But fame is a radically different experience for those who experience it and those who observe it, for better or for worse. Seated beside Diane Keaton in a wine-red lace pantsuit was the singer Billie Eilish, who at the beginning of her career was known for wearing exclusively baggy clothes to help hide herself from the intense surveillance that accompanies celebrity. In her song ‘Everything I Wanted’, the young artist sings about disillusion following desire’s fulfilment. After being granted everything she wanted, the character whose point of view the song is written from finds herself alienated and misunderstood. Her sense of time is distorted. People do not treat her as a human being, as someone with a past and family. Her dream turns into a nightmare. The providence of someone’s love awaits her on the other side of sleep: ‘When I wake up, I see you with me, and you say, “as long as I’m here, no one can hurt you.”’ The nightmare of a mob is fended off by the comfort of one, in a way reproducing the logic of fame which states that the individual is more important than the crowd. The song became Eilish’s second top-ten hit in the United States on the Billboard chart, brightening the spotlight that follows her around.

As much as people are attracted to imagining a carefree celebrity lifestyle full of fun and ease and glamour, tragic tales of woe and falls from grace populate our imaginations as well. Marilyn Monroe, Judy Garland, Rita Hayworth. Why is old Hollywood mythology so full of tragedy? Dionysus was killed by the Titans just as Jesus had to suffer on the cross. We need our idols to suffer because we ourselves suffer. The eternal paradox of fame is this: by being one of the loneliest experiences imaginable, it also becomes one of the most relatable. A culture hyper-fixated on individualism is bound to produce feelings of estrangement and alienation from the surrounding culture and society. Fame represents the apotheosis of both the glorification of the individual and her accompanying isolation. For anyone who feels lost, confused, misunderstood or excluded, fame represents a rare opportunity to turn coal into diamonds. Many people go through life feeling like something is keeping them apart from the world, like there is a key part of reality they can not access. This feeling is extremely difficult to express. When a person is literally ‘set apart’, when they attend parties that no one else can enter, wear expensive clothing that no one else owns, they become expressions of loneliness as well as glamour, because glamour is an expression of loneliness. By endeavouring to make oneself distinct, by way of disposition, appearance and/or ability, a person is able to electrify and magnetise that which sets them apart, to transform a source of frustration into an object of desire. Fame transforms loneliness, one of the most common feelings, into something alien, aestheticised, something that is, in Michele’s words, ‘beyond reach, and yet, so human’.

In addition to the lonely, fame attracts both sadists and masochists, though not exclusively. What greater pleasure is there for a sadist than the knowledge that there is someone out there who would die for you without you even knowing their name? And who better suited to surrender their identity to a beloved ideal than the self-effacing masochist who has buffered and polished their psyche into a perfect mirror? There are those who tell us what we want to see and those who become it. Just as in Greek mythology, Hollywood is full of magic and shapeshifters, those who transform as well as those who are transformed.

Some celebrities possess such a strong, clearly defined perspective and personality that their gestalt and charm overwhelms and hypnotises an audience. Mae West. Bette Davis. Others are more oblique and restrained, those who operate on mystery, cloaking themselves in dark silences and inscrutable smiles. Greta Garbo. Ingrid Bergman. While the former personality expresses her strength and fortitude right off the bat, the latter is no less difficult to maintain – maybe even more so. It takes a great deal of strength to be a mirror. It takes a great deal of intelligence to turn yourself into an effective tool for people to discover themselves in.

Old Hollywood was a strict theocracy, where access to celebrity was limited and gatekept. Studios maintained overwhelming control over the lives of their stars and the way those stars were presented to the public in promotional materials. As social media and the internet have paved new routes to notoriety, the religion of fame has splintered into a vast pantheism, where the deities rapidly change between regions and demographics. Over time we experience less and less common cultural reference points. Because of personally tailored algorithms and internet sub-subcultures, everyone has their own idea of who is famous, who is worth paying attention to, who is universal.

The Gucci Love Parade was, in part, one attempt at reestablishing a canon, enshrining the pantheon, with an emphasis on the star as a figure of immense mystique and bullseye for arrows of envy and desire. One of Alessandro Michele’s muses, the actress Dakota Johnson, belongs to a bona fide Hollywood aristocracy and was well positioned for fame at birth. Her mother is actress and Oscar nominee Melanie Griffith and Melanie Griffith’s mother is Tippie Hedren, the iconic ‘Hitchcock blonde’ and star of that director’s classics The Birds and Marnie. Johnson has now become a star in her own right, most recently appearing in Maggie Gyllenhall’s The Lost Daughter, carrying on the family legacy. While many are quick to derisively cry ‘nepotism’ whenever they hear of an actress with famous parents, I am actually rather fond of the idea of children carrying on the legacies of their forebears, especially when it comes to creative endeavours. A craft, an art, inherited by blood. Lineage. History.

There are also those who do not come from such a background and break through to the stratosphere of fame regardless. Tyler the Creator, Odd Future enfant terrible turned multi-hyphenate creative savant, released his early music independently, without label backing. Through absurdist antics, shock value and undeniable talent, he gained recognition and has, over time, attained a career and prestige that has made his early critics eat their words. Now he attends Gucci shows wearing an ushanka, brown puffer jacket and shorts, leather loafers with white socks, a saint of originality.

The power of fame to reshape one’s life and repudiate enemies is no doubt one of its shiniest lures. For some people, the ultimate fantasy of fame is not about possessing material wealth or easy living, it is the thought that if they were to become famous, then every humiliation, every taunt and sacrifice and insecurity they have endured over the course of being alive would be given new meaning, reversed and inverted, that all shame and reproach would drown in a sea of light from flashing cameras. Of course, this is just a fantasy. Fame can also put a target on your back, exposing you and making you vulnerable to anger and hatred from a throng of bitter naysayers shouting in unison like the chorus in a Greek tragedy. Fame is also a test of one’s persistence, resilience and confidence.

Fortunately, to avoid the indictment of bloodthirsty, self-righteous audiences, fame also provides an easy escape hatch. Another one of fame’s many contradictions is the friction between private and public. Some stars try to maintain their privacy by avoiding the press and public entirely. However, the most effective at keeping a part of their lives secret and sacred are those who willingly enact a larger-than-life persona. Once audiences latch onto an idea of who a celebrity is, they stop paying attention to any information that counters their imagined narrative. They establish a parasocial relationship with a character that has been carefully constructed by PR agents and stylists, talk-show hosts and the celebrity themself.

The character of a celebrity differs from their actual personhood and acts as a distraction from reality. It becomes a substitute, a proxy, a scarecrow, or a pincushion for wide eyes to needle into. Constructing a celebrity persona is like setting up a lifelike mannequin or wax sculpture onstage for audiences to marvel at while the sculptor takes a smoke break in the alley out back. In this way, turning oneself into a caricature can actually be a way of sustaining authenticity and humanity in private life. Fans think they know who a celebrity really is, but all they really know is themselves and their own projections.

In the myth of Echo and Narcissus, a nymph who can only speak by repeating the words spoken to her becomes a conduit for a beautiful youth’s self-love. When we look at celebrities, we see ourselves. They are Echo, canvases for our self-fascination.