Head of State’s Taofeek Abijako on design that transcends medium.

Conventions of genre and medium are culturally established by observing the patterns and affiliations of great artists. However, the limits of genre and medium matter as much to a truly creative mind as a sextant does to the distant heavenly bodies it relies on to function.

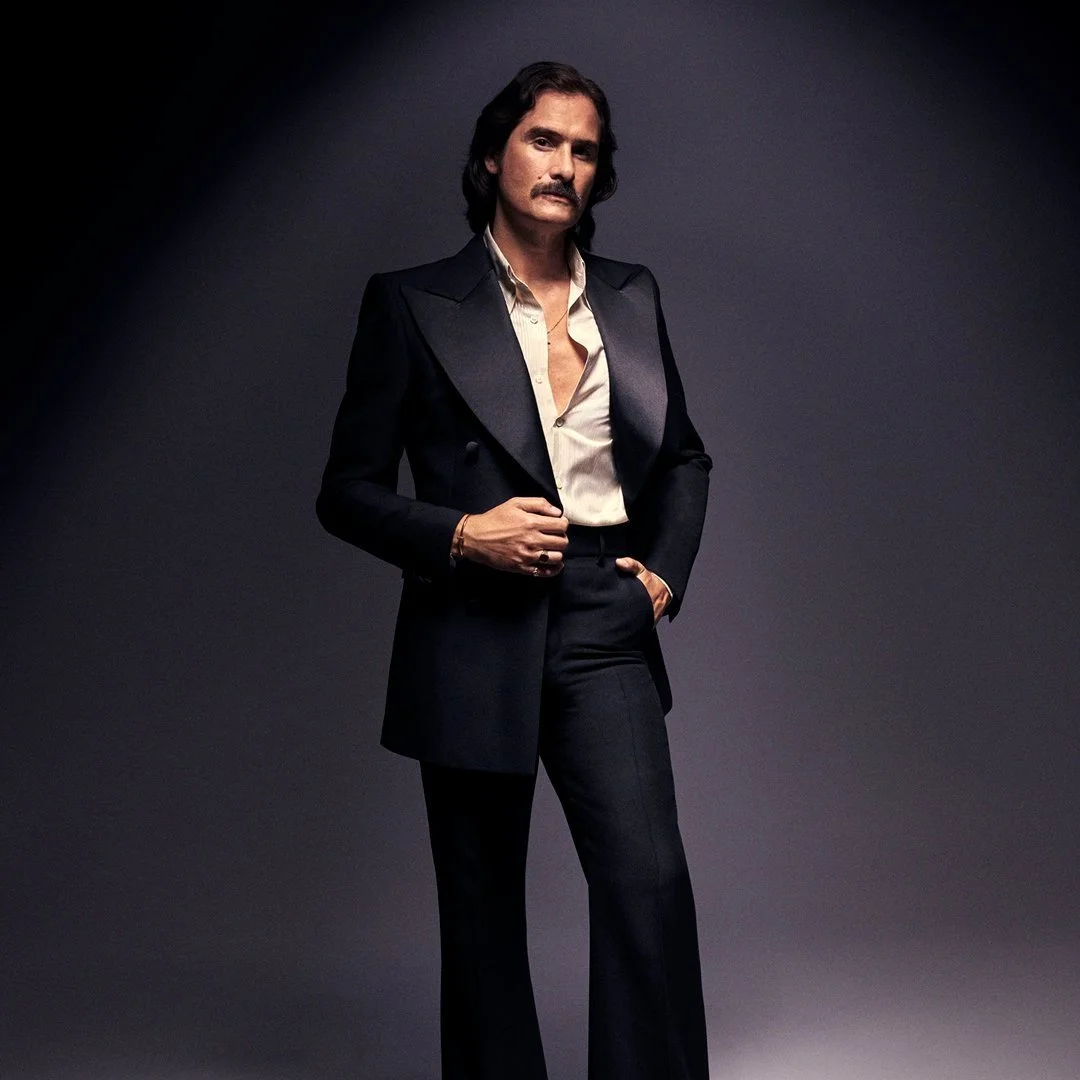

Taofeek Abijako began his brand Head of State shortly after immigrating to New York with his family from Nigeria, and has since expanded the venture into a wide ranging project exploring a variety of mediums and styles. After making his red carpet debut designing looks for stars Evan Mock and Danai Gurira at this year’s Met Gala, the 23 year old designer has his sights set even higher in realizing a total vision of creativity and form that encompasses architecture, clothing, film, and more. I caught up with Abijako in the afterglow of his Met Gala success to discuss both his history and his future as a designer and artist.

Amber: Congrats on your two looks at the Met Gala.

Taofeek Abijako: Thank you, thank you.

Amber: This was your debut, right?

Taofeek Abijako:Yeah. First time ever. It's actually our first red carpet event also. Just went straight for the big one. (laughs)

I found out very last minute. It was less than ten days before the event and at first I thought it was one outfit, then later I found out I was making two. We had a week to make two really strong garments for two very strong characters. We were sewing to the last minute, ten minutes before Evan was supposed to hit the carpet we were still sewing. It was a high pressure situation, so in the moment I was just focused on getting the work done.

Amber: How has the reception been? Has the experience affected your vision for the brand going forward?

Taofeek Abijako: Afterwards, the reception was insane. Evan was on every list you can possibly think of, and Danai looked stunning. It’s something that I want to explore more, showing the consumer we’re not just this brand that does one thing, it’s not just a collection. We can do custom work, we can do something out of the ordinary.

Amber: It may seem like a big jump from the outside, but for you it must have been the culmination of a lot of hard work and smaller steps along the way. Could you walk me through how you got from where you began to now?

Taofeek Abijako: This is a brand I started in 2016. I started Head of State with zero dollars— I got this white pair of vans for Christmas, but I’m so bad at wearing white, so these shoes just sat in my closet. I had some acrylic paint and was like, okay, I need to do something with these shoes.I don’t wear white shoes. So let me paint on these to give them more color and, you know, more life.

I wore them to school and friends were like, ‘oh my God, that looks so cool. Can you make me some,’ and that led me to selling painted shoes.I started also making t-shirts in my little bedroom in upstate New York to fundraise for different initiatives. And that led to developing my first capsule collection. My first collection was getting my hands dirty, running around the garment district, just putting in my 10,000 hours, which I’m still putting in, I would say.

My senior year this Japanese retailer called United Arrows reached out. They came across my collection online and they were very interested in setting up a meeting. That was the first major break. They placed an order and that led to a multi-season relationship with them. I was able to expand on my product offering and that led to me doing a presentation, and then a fashion show on the men’s calendar. Awards went around and eventually, fast forward a couple years, I debuted on the official women’s calendar, which was last September.

Amber: You started designing t-shirts for fundraising initiatives, how has that ethos persisted as your brand has grown?

Taofeek Abijako: Yeah. I was applying to colleges. I wanted to study fashion and architecture, majority architecture. The school I wanted to go to required me to put together a portfolio, so I decided to fundraise for this neighboring community that my parents grew up in that needed access to an efficient water system. I was like, okay, I can make a little collection, build my portfolio and fundraise for this project. That’s evolved to now, where every collection we put out has to have an initiative attached to it. So some of the initiatives include what we’re doing in Nigeria, and also what we’re doing here in the US. In Albany, New York, we’re currently in the process of building a community center.

Amber: On your website, you talk about Head of State being a representation of “postcolonial youth culture today”. Could you expand on that a bit and talk more about what postcolonial youth culture looks like to you? Who do you see as your peers, internationally?

Taofeek Abijako: In a way, I’m a part of it. Nigeria got its independence in 1960, and as a response there was civil war, but what also happened was there was this counter culture that was created around that time period where young Nigerians were blending traditional culture with Western culture imported from colonialism and creating this new language, which led to the current youth culture in West Africa.

This led to important artistic movements that we see now. Like with music, we see the rise of Afrobeat, which came from young Nigerians blending traditional sound and marrying it with Western influence. In fashion, photographers in Western Africa, like Malick Sidibé or Seydou Keïta, captured the clash between Western influence and traditional culture. I’m very interested in that time period, because I feel like I belong in that currently. I grew up in Nigeria, I spent half of my life there and then I’ve spent half of my life in the US. So in a way I’m a new man between these two different environments, and it’s a fascinating space for me to explore. There’s a lot of stories to be told about it, a lot of nuances you can explore as an artist.

Amber: As you started being in communication with international retailers and a broader global audience, did those exchanges or interactions continue to shape your aesthetic interests or your intentions with design?

Taofeek Abijako: My story is very personal to me, but there’s also millions of people who come from where I’m from who relate to it. I’ve realized it’s a story that transcends all different walks of life. So if you’re a kid from India who moves to the US, or a kid from Japan who moves to the US, or vice-versa, you can find something similar in the story that Head of State is telling.

When people think about African culture, they think of this stereotypical, “oh, you’re making prints, you’re making these loud garments with patterns.” But what I actually took from my culture back home was a silhouette, the way shapes are made. I marry that with my Western influence which is why the clothes are familiar here. If you’re from the West, you go, ‘okay.’ It’s still familiar in a way. That’s why my consumers have been so diverse. My story isn’t limited. You don’t have to be from Nigeria to relate to it, you don’t have to be from West Africa to relate to it.

Amber: How did you pick the name Head of State?

Taofeek Abijako: It was actually by accident. My friend and I were figuring out a name, just throwing out random ideas. My phone automatically connected to the Bluetooth in the car and the first song that played was “Coffin for Head of State” by Fela Kuti. Kuti was an early inspiration for the brand, and right away that song made me feel the exact way I want whoever is looking at my work to feel.

Amber: So, music has played a role in your artistic interests, how you express yourself. How do you draw inspiration from other mediums outside of fashion?

Taofeek Abijako: Eventually, people will realize Head of State is not just a fashion brand. I’m interested in a diverse range of mediums. When I started the brand, it was actually supposed to be an architecture project as well. I recently started costume designing for movies, which is another part of the brand I want to explore. One of my past collections was centered around a book by Chinua Achebe called A Man of the People— I dissected the book and each look was inspired by a different character. It was my interpretation of what they would look like in a modern context. I try to find a diverse range of influence from different mediums to feed into the story I’m telling.

Amber: I didn’t know you began with an interest in architecture. That’s interesting to me, because architecture and fashion are related, I think, in that both are about inventing living spaces, whether it’s a room that you inhabit or clothing that you inhabit. There are exceptions, of course, but by and large buildings and clothing are designed with a very practical intention. How does your interest in architecture carry over to your clothing design sensibility?

Taofeek Abijako: Most of my mentors come from architecture. I took an extra long gap from going to school so I can focus on the brand, but I do plan on studying architecture full time. I’m not a licensed architect so I can’t build at a firm, but I’d like to partner with people who are, who have that extensive experience. That’s something I really want to explore for my next collection. To give you a little clue of what I mean, the next collection is inspired by memories from home. So what does that look like? The spaces I grew up in, the environment I grew up in, from the texture to the shape of the buildings, I want to replicate it in the silhouettes of the garments.

I look at both mediums in a sort of exclusive way, architecture for architecture and fashion for fashion, but when I try marrying them together, it’s something that I'd say the brand is still trying to figure out the language for. What is the marriage of fashion and architecture for Head of State? During COVID we did a pop up in upstate New York, and it was me building this collapsible pop up space that disappears over time. We had these modular furnitures that you could stack in different ways. The idea was for every purchase of a Head of State shirt you got a piece of the furniture and then saw this outdoor shop disappear over time. I want to explore, what does a temporary retail space look like? Imagine going to an event like Art Basel and doing the same thing, a timelapse of setting up this outdoor space that will disappear over time and leaves no carbon footprint, which is something we have to be very mindful about.

I don’t want to explore it just in a way like, ‘oh, this t-shirt is inspired by this building’, even though that’s something that I’m doing too, I don’t want it to just be so literal. I want to form new languages, and that pop up is a perfect example of a new language the brand is trying to put out there.

Amber: Who are some of your architectural inspirations? If you could live in a home designed by anyone, who would it be?

Taofeek Abijako: The person I worship the most across the medium is Francis Kéré. He’s my favorite designer ever, actually. He’s not a fashion designer, he’s an architect, but I think his philosophy for how he goes about his buildings can apply to any medium. He’s from Burkina Faso and he recently became the first African to win the Pritzker Architecture Prize, which is like the equivalent of the Nobel prize for architecture. His story is actually very similar to the book I mentioned earlier, A Man of the People. This is a young guy who grew up in Burkina Faso. The entire community came together to send him to school in the West. Eventually he achieves this higher education, then he comes back and can help the community.

When he came back to Burkina Faso, he came up with this new way, this groundbreaking idea of how buildings in marginalized spaces should be made. I’ve been studying his work nonstop since I came across it. How do you make buildings in spaces that you wouldn’t expect those types of buildings to be in, and how do you make them while being mindful of the culture that exists in that space? The same way people are Beyoncé stans or Rihanna stans, I’m the biggest Francis Kéré stan out there. That’s easily someone I can say is a big inspiration for me. He’s incredible. He’s always pushing the expectation of what buildings should look like.